My great-grandmother Eudora was a calculus instructor at Ohio State and a fan of Martin Gardner’s Mathematical Games column in Scientific American. One of the concepts that Gardner introduced to a larger audience were Polyominos, extrapolation of dominos with larger numbers of squares. The shapes in Tetris are pentominos; they are shapes made up of 5 squares.

Eudora introduced Gardner’s column to my mother, Donna, who was also became a fan of recreational mathematics. In November, 1987, she saw this article in Science News:

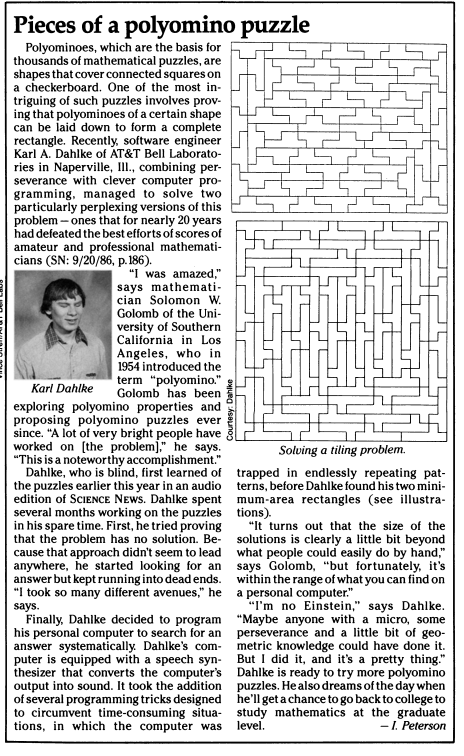

Pieces of a Polyomino Puzzle

Polyominoes, which are the basis for thousands of mathematical puzzles, are shapes that cover connected squares on a checkerboard. One of the most intriguing of such puzzles involves proving that polyominoes of a certain shape can be laid down to form a complete rectangle. Recently. software engineer Karl A. Dahtke of AT&T Bell Laboratoties in Naperville, Ill., combining perseverance with clever computer programming, managed to solve two particularly perplexing versions of this problem — ones that for nearly 20 years had defeated the best efforts of scores of amateur and professional mathematicians. "I was amazed," says mathematician Solomon W. Golomb of the University of Southern California in Los Angeles, who in 1954 introduced the term "polyomino". Golomb has been exploring polyomino properties and proposing polyomino puzzles ever since. "A lot of very bright people have worked on [the problem]" he says. "This is a noteworthy accomplishment."

Dahlke, who is blind, first learned of the puzzles earlier this year in an audio edition of Science News. Dahlke spent several months working on the puzzles in his spare time. First, he tried proving that the problem has no solution. Because that approach didn't seem to lead anywhere, he started looking for an answer but kept running into dead ends. "I took so many different avenues," he says.

Finally, Dahlke decided to program his personal computer to search for an answer systematically. Dahlke's computer is equipped with a speech synthesizer that converts the computer's output into sound. It took the addition of several programming tricks designed to circumvent time-consuming situations, in which the computer was trapped in endlessly repeating patterns, before Dahlke found his two minimum-area rectangles (see illustrations).

"It turns out that the size of the solutions is clearly a little bit beyond what people could easily do by hand," says Golomb, "but fortunately, it's within the range of what you can find on a personal computer"

"I'm no Einstein," says Dahlke. "Maybe anyone with a micro, some perseverance and a little bit of geometric knowledge could have done it. But I did it, and it's a pretty thing."

Dahlke is ready to try more polyomino puzzles, He also dreams of the day when he'll get achance to go back to college to study mathematics at the graduate level.

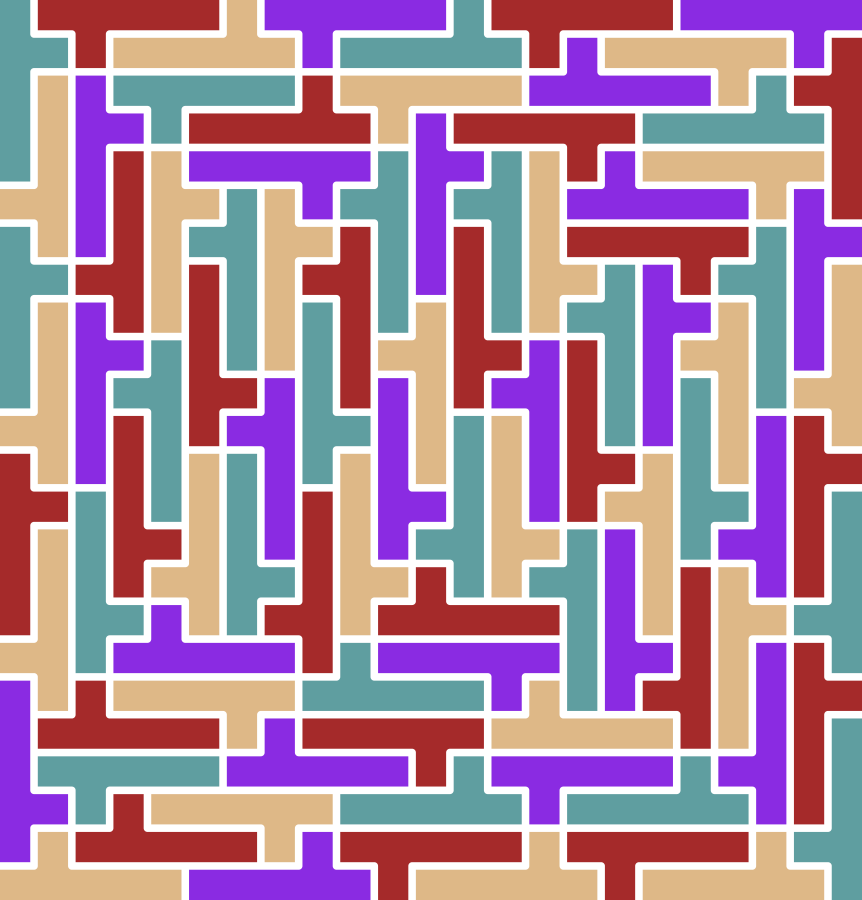

My mom made quilts of these two tilings between 1987 and 1989, which was impressive because I was born between the two quilts.

The quilts hung in the dining room of my childhood home. I spent many hours staring at them instead of practicing piano (sorry mom). When my parents downsized after retirement, they gave me the quilts, and they now hang in my bedroom. My baby loves looking at the quilts because they are bold colours with sharp edges. As a project while my baby sleeps in my lap, I have been translating/recreating Dahlke’s original C code into Python so that I can generate vectors of the tiling for use with a die cutter, embroiderer, etc.,

Dahlke has hosted his pentomino packing code on his website, but not, as far as I know, the code that originally generated the heptomino/hexonimo tilings above. I used the packing algorithm in Dahlke’s pentomino code but with the 8 orientations of the piece instead of all permutations of the pentominos and their orientations. The packing algorithm is:

- create a grid with a margin of size 2 around the edges. Fill the margins with a negative character.

- find the topmost leftmost unoccupied location in the grid, and see if any pieces, defined my their topmost leftmost square, can be placed in the board. The margins prevent pieces from being placed partially off the edge of the board.

- if no piece can fit, remove the last placed piece, and repeat step 2 with the next unused piece

- if there are no more empty locations in the grid, the board must be filled, therefore we have a solution

Using a single thread of my core i7 7700k, this algorithm takes 3.5 hours to find the hexomino solution, and 7 hours to find the heptomino solution. Given that this code took 3 days in the late eighties, and consumer grade computing hardware has grown exponentially in the meantime, this time is a bit disappointing. Granted, I have not studied the problem for nearly as long as Dahlke, so there are probably several things I could do to constrain the search space, which I suspect is what Dahlke did.

Here’s somethings I tried to cut down on the execution time:

-

parallelization: This problem does not have an obvious way to divide the search space evenly, so does not parallelize easily. I could use an evaluation queue for potential solutions, but the time cost of passing information between processes eclipses the time to evaluate each placement.

-

CSPs: I tried formulating the problem as a constraint satisfaction problem, to take advantage of numerical optimization techniques that have been developed since the 80s, but this ran for days without finding a solution. I suspect I haven’t set up all the necessary constraints.

-

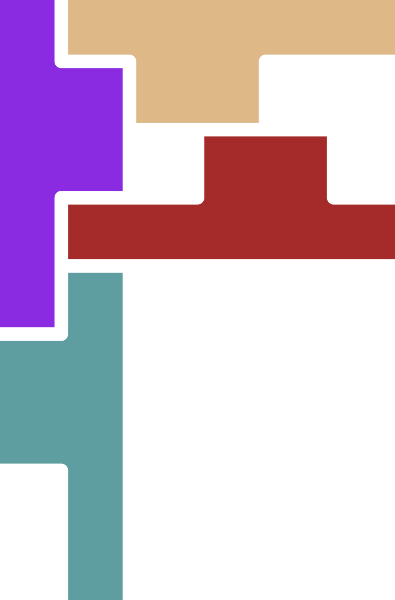

removing holes: there are some placements that create holes that obviously can’t be filled by another shape. For example, if you place this heptomino sunny-side-up will create a hole in the next column that can’t be filled in by any piece:

Thus, if the grid location two up and one to the right of the current location to be filled is occupied, this sunny-side-up piece can’t be placed. This cuts down the search space. I identified at least one grid location to check per piece orientation for the heptominos. This cut down the time to find the first solution to 1 hour. However, identifying and coding these rules is time consuming. It feels like there should be a way for the computer to automatically detect hole-creating placements, but I haven’t found how.

My code is available on github. Dahlke requested that his pentomino packing code be used only for personal use, thus these scripts are distributed with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 3.0 Unported (CC BY-NC 3.0) license.